“We Are Poor but So Many”: Self-Employed Women’s Association of India and the Team of the Platform Co-op Development Kit Co-Design Two Projects

Last month, after a year of preliminary conversations, the team leading work on the Platform Co-op Development Kit launched a collaboration with the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) – the largest organization of informal workers anywhere in the world. SEWA, a union of 1.5 million members and a federation of cooperatives with over 300,000 members offering services such as child care and insurance, is headquartered in Ahmedabad but operates all across India, organizing poor women workers in the informal economy.

By partnering with our team as one of five pilot groups for the Kit, SEWA Federation will be able to co-design two projects. One will provide a democratic governance tool for the members of the co-ops that work under the SEWA umbrella but are geographically too far apart to meaningfully participate in its activities. The second project is a platform co-op for beauty services.

About Sewa

SEWA union launched in 1972 with a small group of women who wanted to secure micro-loans to start their own businesses. Having been told they were “not bankable” by the nationalized state banks at the time, founder Ela Bhatt helped them learn to launch their own bank. By pooling their resources, and with contributions as little as ten rupees from many women in the community, SEWA established its own cooperative bank in 1974 with 100,000 Indian Rupees, or slightly more than 1377 U.S. dollars. The women began to recognize their own power. Ela Bhatt’s first book was consequently titled “We Are Poor but So Many.” Next, the women turned their attention to reducing medical expenses, as they were proving to be an obstacle to the women paying back their loans. Within a few years SEWA created a healthcare cooperative, which now provides affordable medicine. More and more enterprises continued to develop under the cooperative model. And while SEWA focused first on organizing urban women, they eventually also expanded into rural areas.

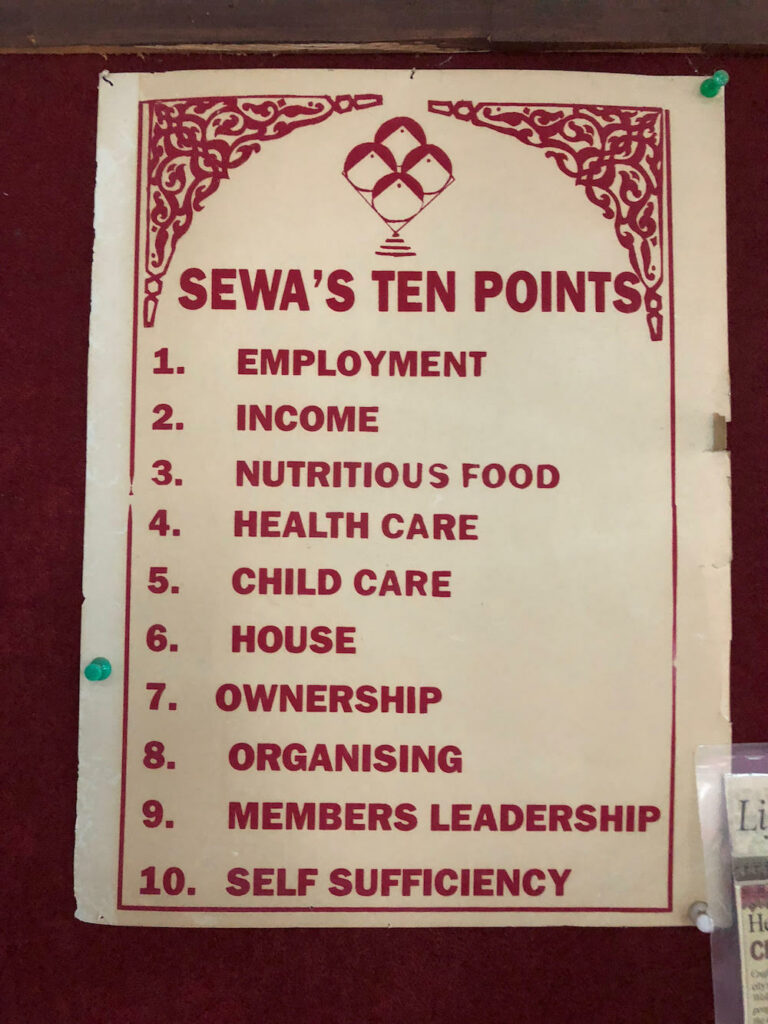

Today, Sewa Federation is comprised of 106 cooperatives, working in industries such as milk production and financial services, prescription medications and garment manufacturing. Importantly, Sewa Federation is a multi-denominational enterprise with women from various religious backgrounds: Muslim, Hindu, Christian, Jainist, and Buddhist. Sewa offers a range of services: from education to catering, childcare, and other services. The key to SEWA’s success has been its integrative approach, centering an entire ecosystem of co-ops around the needs of poor self-employed women in the informal economy. Learn more about SEWA’s unique approach through this report from the International Labor Organization (ILO).

We are grateful to the ILO for introducing us to SEWA.

Building A Beauty Services Platform Co-op

The collaboration with SEWA Federation is planned for the next two years. The platform co-op for beauty service will allow users to request a worker-owner to come to their home to do makeup, threading, waxing, and haircuts or massages. The platform will meet a growing demand for home services in the beauty sector in Ahmedabad and other Indian cities, as evidenced by the growth of extractive platforms such as UrbanClap and VLCC.

During his trip to SEWA to discuss this platform, Trebor Scholz met with both Namya Mahajan, managing director of SEWA Federation, and an initial cohort of 25 women who are currently being trained to work through the platform co-op. Learn more about the Federation’s commitment to the project in this short video with Namya:

When Trebor joined the workers in their first training session, they were learning how to greet a client at their home by stating their name, which was new to them as it is not common for low-caste women to state their names. Interestingly, many of the women already own or have access to smartphones. They are also familiar with Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram. But scheduling their work through a platform co-op will be new to them.

In discussing what they would like to see in the platform co-op, the young women emphasized their concerns about safety when traveling to clients and working in their private homes. In the workshop, the women asked for a panic button for workers to be integrated into the app. The button would allow them to quickly alert two friends and the police in case of an emergency. One of the more experienced beauty workers strongly felt that there should be no individual worker profiles available to customers. In order to protect the women from assault and harassment, users of the app should have no choice over which co-op member who is providing a particular service. They also expressed interest in a GPS feature that would allow a co-op manager to know their whereabouts.

By December of this year, once a prototype has been completed, work through the platform can begin with 25 women workers. A second group of 50 women will then begin the training, to join the platform in March 2019. The goal is to upscale the platform to anywhere between 500 and 1000, the average size of a SEWA cooperative. In contrast to the 30% of the revenue extracted from workers on traditional platforms, SEWA Federation only plans to take 15% to cover administrative and educational expenses. If successful, the platform co-op could even expand to cities like Patna, Chandigarh, and Delhi. Finally, because the women will be working in the clients’ homes, the platform could eventually offer other household services like cleaning, child care, painting, plumbing, electrical work, pet care, carpentry, cooking, and waste collection.

Additional support is coming from Godrej Consumer Products Limited. Godrej is contributing the initial capital investment for the business. It also supports the training for the beauty workers through curriculum.

Strengthening Distributed Co-op Governance

The second platform for SEWA will focus on organizing the cooperatives of the SEWA Federation spread out across the state of Gujarat, and additional cooperatives all across India. Distributed democratic governance is a significant challenge for many cooperatives, and given the number and diversity of co-ops within SEWA, and their geographic distribution across the entire state, SEWA needs a new online tool to help them organize, educate, and make decisions. Just think of the Adivasi women in the remote parts of the mountains in Southern Gujarat. While new tools like Enspiral’s Loomio saw amazing uptake, distributed democratic governance remains a big challenge for co-ops worldwide. But if trained to use technology and given smartphones, the women led by village elders could co-govern the co-op from afar. First conversations led us to imagine such functionality, also useable on flip phones, as follows:

• A decision-making tool in which co-ops can vote and decide on strategic matters and resource distribution within the federation

• A social-networking tool in which cooperators can connect and message each other

• An educational resources tool in which SEWA can share new videos, manuals, instructions, and best practices directly with co-ops, and co-ops too can share business information directly with the SEWA umbrella organization

These services, still pending the co-design process, would allow for improved business practices and stronger democratic governance for SEWA Federation across Gujarat. They could collect data from co-op members that could then be shared with policymakers, for instance. Thus, the tool could impact state policies so that local and national governmental policy better serves the interest of co-ops. The platform will also need to respond to the many different languages spoken by cooperators in the region (e.g. Gujarati, Hindi, English, etc.) and incorporate audio tools. In short, a new governance tool would dramatically improve the functionality and effectiveness of SEWA Federation.

More applied research in the area of distributed governance among precarious in the informal economy is much needed.

Sewa Federation is also interested in a cooperative online marketplace that would allow some of their co-ops to sell artisanal products, snacks, garments, generic medicine and Ayurvedic medicinal products.

In November, the Inclusive Design Research Center will start leading co-design sessions with women workers in Ahmedabad and then develop platform prototypes based on their specific needs. Trebor discussed with SEWA’s own video production cooperative the production of a series of testimonials documenting this process, interviewing workers in co-design sessions and creating videos in which women discuss their experiences with the platform co-op. Through the documentation of workers’ experiences, the videos will capture the potential of this model.

Learning from Sewa

The key to SEWA’s success has been their holistic, federated approach. SEWA places poor women workers in the informal economy at the center of an ecosystem of co-ops that seeks to address their various social needs, not just economic necessities.

In the U.S., many long-standing, very large and wealthy cooperatives have lost the focus on support for those who need it most. While large consumer, purchasing, and agricultural cooperatives like REI COOP, Ace Hardware, and Organic Valley prove economically successful and sustainable, they fail to significantly address broader social problems. They do not tackle complicated social and economic needs, like full-time workers lacking healthcare, rising income inequality, soaring childcare costs, etc. Workers in such co-ops sometimes do not exercise or feel inspired to participate in democratic governance.

By understanding and learning from SEWA, workers and cooperatives elsewhere can envision new ways of organizing their workplace, and re-orienting their cooperative identities. For example, larger U.S. cooperatives could commit to the 7 cooperative principles (especially the one focused on co-ops helping other co-ops), by investing in new startup projects (including platform co-ops) and creating spaces for incubation. They could also make a real commitment to open source tools, so that new platform co-ops do not have to waste resources and reinvent the wheel. By carrying SEWA’s integrated approach to the gig economy, we can imagine a stronger cooperative ecosystem that addresses the social and economic needs of workers in the informal economy, which account for over 90% of the Indian economy.

We are excited to be co-leading this work with SEWA over the next two years. As always, write to us if you would like to contribute (info@platform.coopersystem.com.br).

Check back on this blog for more updates as the work progresses.