We Stand In Solidarity with Striking Ride-hail Drivers in India

Uber has frequently been in the news for its abuses of its employees and customers, from the recent documentation of the omnipresent sexual harassment at the company’s San Francisco offices by Susan Fowler to the tracking of passengers by Uber employees — ex-girlfriends, celebrities, and politicians. After CEO Travis Kalanick made a public statement in defense of the company’s relationship with the Trump administration, over 200,000 users mobilized under the slogan #DeleteUber and uninstalled the app.

What has been less documented in the news, however, are Uber and other ride-hailing platforms’ persistent abuse of their workforces. Drivers are classified as independent contractors, not employees, such that they are denied basic protections such as a guaranteed minimum wage, health care and other benefits, and the right to collectively bargain. This power asymmetry allows transport network companies like Uber to attract drivers with high wages, only to slash them without warning once a hold on a market is established. Last December, drivers in Paris struck in response to falling wages, blockading access to Paris’ airports. U.S. based drivers have struck a number of times, including a nation-wide strike last November. U.K. drivers, among others, have also begun to fight back, going on several strikes and ultimately winning a landmark court case which redefined them as workers — rather than “self-employed” — entitling them to holiday pay, paid rest breaks, and minimum wage.

Since late December, drivers for the ride-hailing apps Uber and Ola have been engaged in on-again off-again strikes across India. Strikes began on December 31st in Hyderabad in response to falling earnings, unfavorable incentive restructurings, and the continued onboarding of new drivers which has increased competition for passengers. While that strike ended on January 4th due to the intervention of the court, agitation across the country continued until earlier this month when drivers went on strike in the National Capital Region of Delhi, and the cities Hyderabad and Bengaluru.

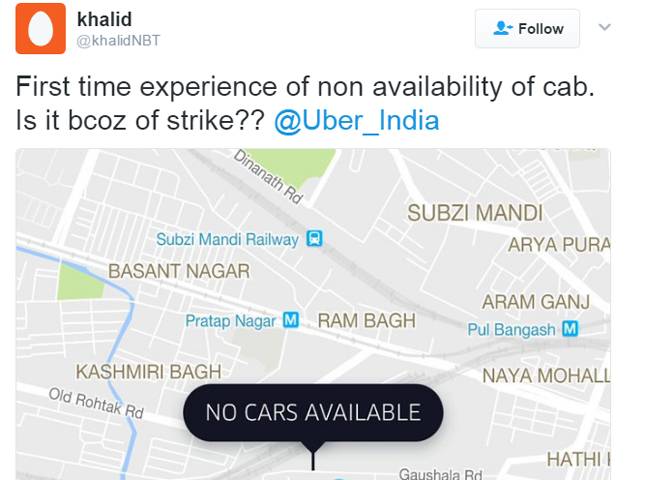

Over 100,000 drivers have refused to log into their apps in Delhi-NCR since February 10th, with wait times for commuters reaching up to an hour. The Sarvodaya Drivers Association of Delhi (SDAD) — sarvodaya, “universal uplift” or “progress of all” — served as an informal organizing body for the strike, representing 150,000 Delhi-NCR drivers in lieu of a traditional union. An estimated 95% of drivers in Bengaluru joined the strike on the 21st, while drivers in Hyderabad have been gathering in public protest around the city for months. The strikes have exerted an immense amount of pressure on Ola and Uber, the former of which appears ready to come to the bargaining table, as well as various regulatory bodies which appear to be at wit’s end with the transport network companies. “We have met with them thrice now, but they haven’t addressed even a single demand by the drivers. All they do is buy more time on every occasion,” said Karnataka State Transport Commissioner MK Aiyappa.

The Delhi strike was halted after 13 days last Thursday, February 23rd, as drivers prepare to present their grievances to the High Court on February 28th. The strike will continue the day before, building momentum going into these negotiations. Lovkesh Sharma, a driver for Uber and Ola, discussed the impetus for the strike:

The company had earlier promised us a minimum income of Rs 100,000 per month. Though we never achieved that target, we still made a decent income till six months ago. But with time, the companies kept changing their incentive pattern for every driver and with that our incomes have reduced to such an extent that we fail to save anything after paying all the dues, including installment for the car loans.

These strikes center around falling wages for drivers on the Uber and Ola platforms, caused by a number of changes made by the ride-hailing companies, with some workers seeing their earnings reduced by up to 50%. Most frequently discussed is the pay-per-kilometer earned by ride-hail service drivers: while autorickshaws make Rs 9/km and licensed radio cabs make Rs 23/km, drivers for Uber and Ola make only Rs 6/km. With the addition of ride-sharing features such as uberPOOL, drivers can make as little as Rs 3/km, just 15% of the Rs 19.50/km mandated by local legislation in the state of Karnataka.

Though pay-per-kilometer has long been low, drivers are offered incentives based on number of rides they give in a day and the time they spend idling on a platform while waiting for their next fare. However, these incentives were restructured early this year to revolve around “earnings targets” which must be met in a specific period of time to qualify for the bonus. This new system forces drivers to work for long stretches and does not compensate them for the time they spend logged into an app. In addition, a 25% commission has been introduced by both platforms, 5% of which goes to the state. One driver, Amit Kumar, was frustrated by these changes: “I worked for 22 hours and achieved the target. But they cut commission from that too.”

As Uber and Ola fight for market-share, they have been hiring new drivers at an unprecedented rate, further reducing drivers’ earnings. Insofar as many drivers on these platforms do not own their cars, but rather lease them from Uber or Ola, this increased competition has proven untenable. “First, they induced us to buy cars under their schemes now they are adding so many new cars that it has become difficult for us to pay off our monthly installments.”

The drivers’ primary demands are thus an increase in pay-per-kilometer, the elimination of the 25% commission, the end of ridesharing (the government of Karnataka has given Uber and Ola two weeks to remove these features from their apps), a moratorium on new driver registrations, and an idling pay of Rs 3/min. The drivers’ other demands, however, are equally pressing. They are calling for a relaxation of working hours, with drivers currently spending 18 hours or more on the road, the creation of 24/7 call centers to increase these companies’ accountability, and the elimination of the Rs 1,000 fee that drivers are charged when they receive negative customer feedback, often for “offenses” like refusing to let passengers smoke in their vehicles. Drivers are also seeking health and accident insurance, spurred by the January 22nd death of an Uber driver, Nazrul Islam, when his vehicle was struck by a speeding BMW; drivers were outraged when Uber refused to offer financial assistance to Islam’s family.

The 13-day strike has seen drivers engaged in a number of direct actions, including demonstrations, hunger-strikes, an attempted suicide outside of the Ola offices, the ransacking of the Ola and Uber offices, and the vandalization of cabs which have continued operating. Though many drivers say that they will continue to strike indefinitely, nearly two weeks without pay has put pressure on them to return to work. “At the end of the day, we have to feed our families, manage school fees for the children and pay installments on our car loan,” said one driver. The financial pressures felt by drivers have been exacerbated by Ola and Uber, which have sent repeated text messages to drivers reminding them that their lease payments are coming due, in hopes of breaking the strike. Shortly after the strike began, Ola informed them that it would reduce their lease payments only to rescind that offer, blaming the ongoing strikes. “I had no option but to start driving again, so that I can earn and pay,” said Arun Shah, who bought his car through Ola’s financing service.

It is clear that the long days, low pay, and horrendous working conditions are untenable for India’s on-demand drivers. They labor, as do other ride-hail drivers worldwide, under what can only be described as a modern-day system of indentured servitude; drivers are stuck working for these platforms due to leases taken out on cars under the false promise of high earnings. Uber and Ola and other TNCs have externalized risk to their drivers, in standard platform-capitalist fashion, by failing to offer even a basic safety net for drivers and their livelihoods. As the concurrent abuses by Uber and Ola show, this is not a problem that will be solved by switching from Uber to Lyft, substituting one exploitative firm for another. There is a pressing need for worker-owned apps that treat workers fairly and pay them an ethical living wage. Platform cooperatives like Green Taxi Coop, Union Taxi, People’s Taxi, and LaZooz have already proven the viability of this model, even in market-competition with dominant TNCs.

With the strike in Delhi-NCR resuming on Monday, the Platform Cooperativism Consortium stands in solidarity with those bravely declaring that enough is enough. Across the world, we will not let the gains of 100 years of labor struggle vanish without a fight.